LETTER TO THE EDITOR

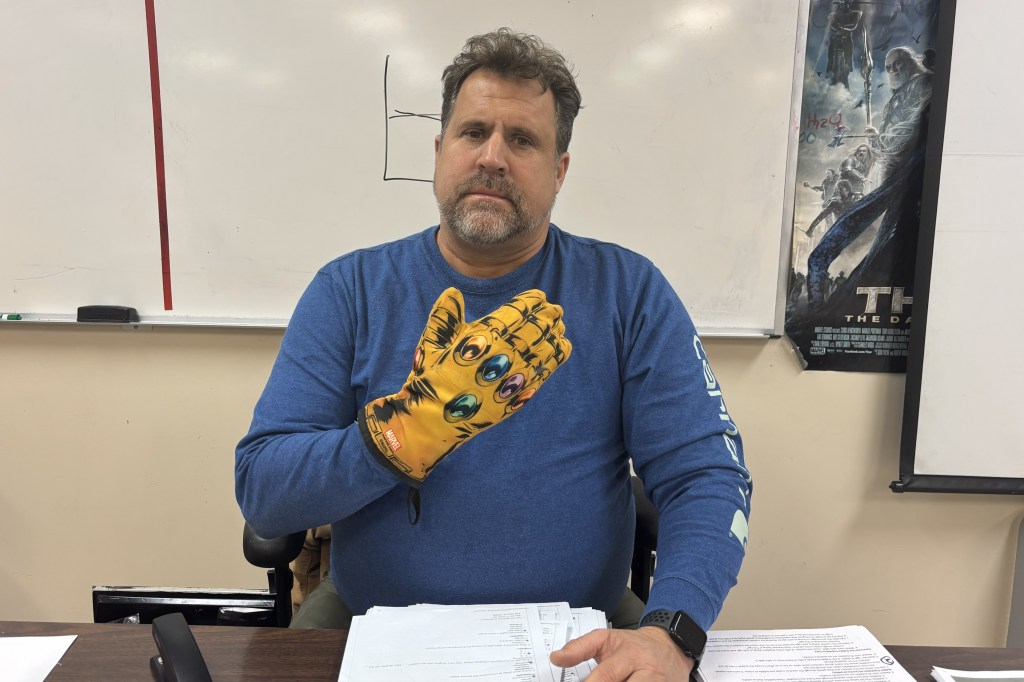

Michael Faragher received his B.A. in Disaster and Emergency Management from the American Military University in 2012. He graduated from West High in 2001.

There’s been a lot of discussion about the incident in the West Bend High Schools in the past 24 hours. Having not been a student there for nearly 14 years, I heard about it indirectly, but I did get to see my fellow alumni voice their opinions, and immediately forget they did worse when they were in the same position. In 1999 or 2000, we attempted to organize a walk-out in solidarity with the teachers against the administration. I was hauled into the vice-principal’s office, and when I told him I hadn’t distributed the fliers I’d made yet, he visibly relaxed and said they were very well done. Apparently, if that happened yesterday I may have been arrested. But I’m not here to discuss the ways I think the school might be mishandling some things, I’m only discussing how they’re mishandling one thing: this situation.

I’m professionally aghast at the school’s reaction. I’ve designed enough emergency plans to see that what happened was a massive failure of any plan they did have. Non-violent children running through the halls does not require over a dozen officers from a department so small. The worst part is it was completely avoidable. Most of the discussion from the students revolves around it not being about the hall passes so much as the general treatment of the student body.

During the riots in Ukraine, I was in constant contact with several people involved. It started with police smashing cell phones and cameras at a peaceful protest, and eventually spiraled out of control into the situation in the nation today. There is unrest in Hong Kong, Mexico, and Ferguson, and they all follow the same pattern. The protestors make demands, the administration overreacts, and then the administration makes concessions. This is the constant pattern across all civil unrest, and, even without discussing it with students, I can largely assure you that the school has put into place new rules or told their teachers to put their foot down. It is how things are done.

It’s not really the school’s fault. They’re educators and administrators. None of them even considered that there would be any action, which is why they panicked when any action was taken. The important thing now is that the school sits down and thinks about this rationally. The students are generally unhappy. Kudos for having a forum for them to listen and perhaps voice their opinion, but it’s obviously not enough. This is not the sort of situation where you can simply hold a vote; mob rule in a school is not a good idea. However, the students need a sense of agency, a sense that they’re actually a part of the process, not a number to be graded, paid for, then ejected after four years.

This problem is not recent, and it would be foolish to blame the current school administrators for starting the issues. However, now is an opportune time to see some new initiatives. Allow the students to discuss solutions, find ways to work together. Ask your School Safety Officer about “Community Policing.” I have never seen anyone claim they wanted to go to the high schools, but many do want to learn. There are no simple solutions for the problems regarding the way students are treated, but a dialog is certainly the first step. The students themselves need to take it upon themselves to not disrupt a dialog, but consider the students’ situation from their side.

The administration can do whatever they want, no matter the students’ opinions, can suspend people for even being in the area, can stop discussion or change policy at any time, and then, when they finally can’t handle it anymore, they call the police; the students have nothing but their numbers. The administration has lawyers, superintendents, and many official-sounding people, but they would laugh at a student who wanted an attorney of their own before answering questions. This last bit provides a group with no arrest powers less legal oversight than the police has. Is there any wonder students don’t trust the administration to act in good faith?

The asymmetric power structure generally produces very poor results. Providing agency and a sense of belonging is incredibly important. If a student doesn’t feel they have anything at stake in the system, then there’s nothing to make them want to protect the system. Punishments, individual or group, are generally worthless. Deterrent actions must be swift, certain, and severe, none of which describe any action taken by the school district, and arbitrary punishments make the student the enemy. Give the students a stake, even if it’s only a pizza party if everyone does well. Give incentives, not punishments. Allow for self-regulation, not sterner authority.

This event has done considerable damage to both the students’ and the faculty’s trust in each other and, in some cases, their fellows. A peaceful dialog, or even a simple list of issues of interest, would be extremely prudent at this time. If a problem is ignored, it festers and turns into what we saw yesterday. It is on the administration and the students to find a solution. If one attempts to find one on their own, the cycle will only start again.

Michael Faragher

B.A. Disaster and Emergency Management

The Current welcomes submissions from all students, faculty, administration, and community members, but reserves the right to edit for length or content. Any column, editorial, or letter to the editor expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the entire staff.

Leave a comment